|

| Larry's knife |

In the beginning, prehistoric humans each made their own tools. If you needed a flint scraper to clean a hide, you made it yourself, chipping the edge to make it sharp. And then you used it, after cornering that wildebeest and bringing it down. You created and used your own tools, furthering the chief goal of survival by obtaining food and maintaining shelter and defending the homeland.

But over time, it became clear that one member of the clan

was better at making scrapers and knives than anyone else. Let’s call him

Larry. As the clan grew into a tribe, the chief appointed Larry to make things.

Relieved of hunting duties, Larry churned out the best flint scrapers and

knives in the valley. He traded them for food – the hunters and gatherers fed

him in exchange for his sharp, sturdy tools.

As families grew to clans, clans to tribes, and tribes to states,

specialization became necessary and common. Hunters hunted. Fishermen fished. Farmers

farmed. Weavers wove. Toolmakers made. And traders traded.

The basis for human production and commerce had been

established.

The Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany, chronicles this history

of human activity in a wonderful series of exhibits. The evolution from

early axes and bowed drills to steam powered lathes to the complex computer

controlled milling machines of today is detailed. The exhibits make one thing

clear – humans have excelled in learning how to make things with spectacular

precision and in large quantities.

We have become exceedingly clever at removing material to

achieve a desired result. This is what we are used to. It is called subtractive

manufacturing. To make a wrench, we can start with a blank of steel, cut or

drill out portions we don’t want, and finish the surfaces all to a precise

plan. The wrench emerges from the block by the application of energy and human

intelligence. In similar fashion, Larry’s scrapers emerged from chunks of

flint. Michelangelo’s forms emerged from blocks of marble. And Toyota Camrys

emerge from piles of raw materials.

The common thread in all this is the design, the plan, the

vision, the details of the thing to be built.

We can extract out this essence of the thing, which

describes it in precise detail, and represent it in a computer file. The

dimensions, the angles, the faces, all precisely specified, the thing now

exists, born from our imagination. All we need to do is manufacture it.

But instead of our historical approach of cutting and

drilling and milling, we can now do something novel.

Three-dimensional (3D) printing is a technique for

manufacturing things. Rather than subtractive, it is additive, with thin layers

successively laid down in accordance with the plan, the 3D model, so that the

thing slowly grows into existence. It seems like magic, but only because we are

so accustomed to milling and drilling. But in a way, it is more natural. After

all, cabbages and robins and human beings are all constructed according to a plan

(their DNA) by addition, not subtraction, of materials.

While 3D printing is relatively new, it is rapidly gaining capability.

Entrepreneurs at universities and start-ups are competing to develop

improvements. An Australian company recently announced a new method they claim

will be 25-100 times faster than existing technologies. This will be a race,

and it will accelerate enormously in our lifetimes, driven by advancing

computer power and materials science. It is human magic.

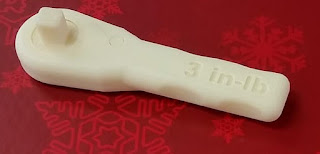

NASA is onboard. In December, the agency emailed a wrench to

the International Space Station. The design file of a ratchet wrench was

transmitted to the station where it was downloaded to a 3D printer. Four hours

later, the wrench emerged. Imagine the importance of this to a future moon base

or Mars colony, where the delay of a resupply mission might be months or years.

|

| NASA 3-D printed ratchet wrench |

How about obtaining a replacement part for an old weed whacker

that’s long out of production? No problem, Lowe’s Home Improvement has

announced that they will soon install 3D printers in select stores. In addition

to predefined design files, you will also be able to send your own computer

models to Lowe’s for printing, and drop by later to pick up the finished product.

We are coming full circle. Soon we might each make our own

stuff, if we so desire, unique to our individual wants and wishes. Larry would

be pleased.

No comments:

Post a Comment